Climate Now Episode 30

October 18, 2021

Pricing carbon around the globe: Why it’s so difficult

Featured Experts

Adele Morris

Former Policy Director for Climate and Energy Economics at The Brookings Institution

Adele Morris

Former Policy Director for Climate and Energy Economics at The Brookings Institution

Adele Morris is a globally renowned expert on climate pricing policies and the former Policy Director for Climate and Energy Economics at The Brookings Institution.

Since the recording of this episode, Dr. Morris became the Chair of the Federal Reserve’s Financial Stability Climate Committee.

Brian Flannery

Visiting Fellow at Resources for the Future

Brian Flannery

Visiting Fellow at Resources for the Future

Brian Flannery is a Visiting Fellow at Resources for the Future, where he continues his work on climate and energy issues from his time at Exxon’s Corporate Research Laboratory where he conducted research and organized international workshops, including on how to calculate corporate emissions.

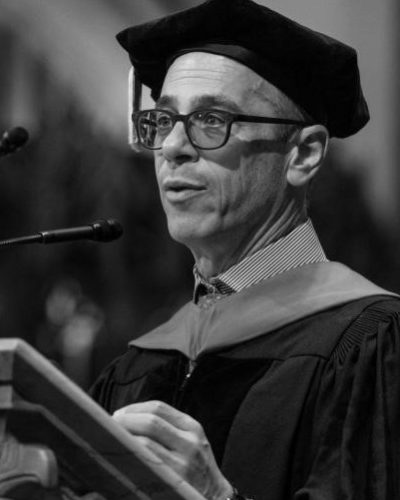

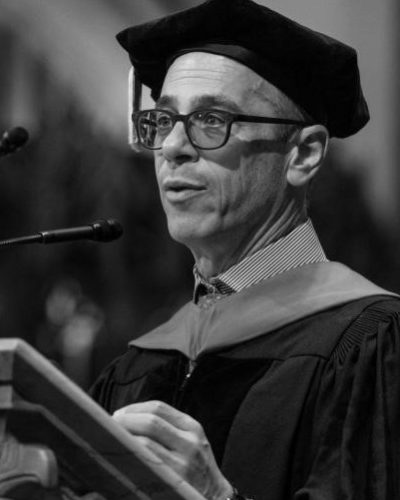

David Weisbach

Professor at the University of Chicago Law School

David Weisbach

Professor at the University of Chicago Law School

Dr. David Weisbach is a lawyer and economist and the Walter J. Blum Professor of Law at the University of Chicago. He is also a Senior Fellow at the University of Chicago Computation Institute and Argonne National Laboratories and an International Research Fellow at the Said School of Business, Oxford University.

Shuting Pomerleau

Climate Policy Analyst at the Niskanen Center

Shuting Pomerleau

Climate Policy Analyst at the Niskanen Center

Shuting Pomerleau is a climate policy analyst at the Niskanen Center, a Washington DC-based think tank. Her areas of research include policy development for carbon taxes. Prior to joining Niskanen, she worked in public policy at the Cato Institute and the American Council on Renewable Energy.

In this Episode

How do we finance the cost of mitigating climate change, while discouraging continued use of fossil fuels? The largest public statement of economists in history argues for a carbon tax – which would charge a fee for every ton of carbon dioxide emitted.

But, if one country charges a different carbon tax than another, what would happen to international trade? Would fossil fuel use and emissions-intensive industrial processes actually decrease, or just move to a country without a carbon tax?

Carbon border adjustments attempt to address these issues, but come with their own legal, economic and practical complexities.

This episode features conversations with Dr. Adele Morris, former Policy Director for Climate and Energy Economics at the Brookings Institution, Dr. David Weisbach, Professor of Law at the University of Chicago, Dr. Brian Flannery, Visiting Fellow for Resources for the Future, and Shuting Pomerleau, Climate Policy Analyst at the Niskanen Center. These experts help us unravel how carbon border adjustments could work, and their role in building solutions to the climate crisis.

Time Codes:

- 0:00 – carbon border adjustment economics

- 13:45 – carbon border adjustment logistics

- 30:00 – carbon border adjustment legality

- 34:30 – carbon pricing

Related Media:

Climate Now: Jul 2, 2021

Climate Policy with Danny Richter

National governments are best-suited to provide the bold, swift action required by the climate crisis through policy. But which policies, exactly, should be passed? What are the pros and cons of each, and which are already proven to be effective in other count

A Climate Change Primer Ep 5

Climate Policy Levers

Which climate policies will help countries transition to net-zero emissions? What are the pros and cons of these policies, and how does the United States compare to the rest of the world in implementing a carbon price? Climate Now spoke with Dr. Danny Richter,

Episode Transcript

TRANSCRIPT

James Lawler (00:04):

You are listening to Climate Now. I’m James Lawler.

Katherine Gorman (00:07):

And I’m Katherine Gorman. Today, we’re talking about what happens when different nations have different approaches to solving climate change. Say a country chooses to impose a larger economic burden on themselves to address climate change than other countries. By doing so, they risk becoming less competitive in the international trade market.

James Lawler (00:25):

One tool designed to alleviate the economic disadvantage of imposing a carbon tax is called a carbon border adjustment. Now these border adjustments are not straightforward. So for this episode, we recruited several experts to help us understand how they work and what the legal, political, and practical considerations are for them to be effective.

Katherine Gorman (00:49):

First, we reached out to Climate and Energy Economist, Dr. Adele Morris from the Brookings Institution, a nonpartisan Washington think tank. And we talked to David Weisbach, a Professor of Law from the University of Chicago with a particular expertise in federal taxation and climate policy.

Katherine Gorman (01:08):

So let’s get some context for why we might need a carbon border adjusted mechanism. Adele, can you tell us a little bit about the kind of economic framework where these border adjustments would fit in?

Adele Morris (01:21):

Yeah. So the basic idea in economics is that greenhouse gas emissions, they’re an external cost of economic activity. So when I put gas in my car, I pay a price that reflects the cost of exploring for oil and producing it and refining it and transporting it, marketing it, but I don’t pay the costs associated with the environmental damages. So the idea of a carbon tax or carbon fee or carbon price is to internalize those costs that are otherwise external to the persons undertaking those activities. And so there’s a few tools you can use, you can use a tax like I described it, or you can also put a cap on emissions and allow companies to trade those allowances. And that forms a market price for the right to emit amongst the covered sectors. And so this is an approach that economists widely advocate, because it provides all these market signals to undertake emissions abatement, and develop and deploy new technologies that will reduce emissions, and it really harnesses the profit motive in a way that helps the environment.

Katherine Gorman (02:39):

Okay, so that’s a great description of the benefits of carbon pricing, but there are drawbacks too. David, can you explain those?

David Weisbach (02:47):

Typically the way carbon prices are imposed is on the emissions in that economy. So smokestacks or tailpipes, right. I think of that as the production occurring in say the United States or the EU or wherever that is. So if you impose a carbon price on production in say the EU, then what might happen, production that’s in a foreign country, not the EU can produce there without the carbon price and then sell goods in the EU for less than goods that would be produced in the EU, which would face a carbon price. So a carbon price on domestic emissions or domestic production creates an incentive to shift production to countries with lower or zero carbon prices, and then import the goods into the home country. And we call that leakage, the shifting of production and the resulting emissions in foreign countries can kind of offset the benefits of the carbon tax in the taxing region.

James Lawler (03:44):

How does then a carbon border adjustment or tax, how might that help correct for this problem?

Adele Morris (03:51):

Well the idea is to ensure that producers of goods that they want to import into the country with a significant carbon price face a similar charge associated with the carbon emissions of those goods that occurs in those countries. And likewise, the producers within the country with the carbon price can export, without being disadvantaged by its domestic regulatory policy. So usually people talk about border carbon adjustments as both charges on carbon intensive import and rebates on carbon intensive exports. And by doing that adjustment at the border, the idea is to reduce the incentive, to shift production, as David described it. Now it’s worth noting that there’s another form of leakage that you can’t really do anything about, and it’s called price-based leakage. So if a big country like the United States shifts back its demand for petroleum in the global market that can reduce the price of petroleum to other countries that aren’t doing that. And they might increase their consumption of petroleum, because the price went down.

James Lawler (05:08):

So it’s clear that leakage limits the effectiveness of a carbon tax on its ability to decrease emissions. But I understand that it’s also important in terms of how it impacts market competition. Can we break down why that is the case?

David Weisbach (05:23):

Yeah. I like to think about what the effect of a border tax is in terms of what we’re taxing. You think about a carbon tax is taxing domestic emissions. And I think of that as production we make when we emit things where we’re producing things, goods or services. And if we add a border tax, what that does is shift the tax to domestic consumption, right? So let me walk you through that. So consider a factory in the US, it’s making something and it can sell the goods here, or it can sell the goods in a foreign country. If we have a tax on emissions, then it doesn’t matter where it sells the goods because it’s producing the emissions here. And so any production here is going to be taxed. And similarly, if a factory were in a foreign country and selling the good in the United States, since it’s not subject to our carbon tax and the carbon taxes on our emissions, then foreign production, wouldn’t be subject to the tax.

James Lawler (06:21):

So essentially the US factory has to pay more to produce the same goods that the foreign factory produces, right? And wherever these factories are selling their products, the US-made product will cost more because it was more expensive to produce the goods in the US with that carbon emissions tax. Is that right?

David Weisbach (06:38):

Right. And supposed we add a border adjustment. So we tax all imports on the carbon content. So any foreign production now would be taxed if the goods are consumed here, not if they’re consumed in the foreign country, and any domestic production is only taxed if the goods are sold here. If the goods are exported, we rebate the tax, right? So if you think about putting it all together, what the border adjustment has done is shift the tax from domestic production to domestic consumption, right? And that’s the reason why it can reduce leakage is because domestic consumption is generally less mobile, it’s not going to shift as much as domestic production.

James Lawler (07:20):

So it becomes a consumption tax because with the border adjustments, the price of a product will reflect the carbon tax in the country where it’s purchased, not the country where it was produced. So, if the US had a carbon price, it would be applied to US production and those factories would then pass that cost onto the US buyer. And then with the border adjustments, a foreign competitor would have to pay an import fee that matches that carbon price so that the cost of their product becomes similar for US buyers. Right? And the US producer would then be rebated on the carbon price so they could stay competitive in the global market. Am I understanding that right?

David Weisbach (08:03):

Right.

Katherine Gorman (08:04):

So David, very few nations have a carbon tax and all border adjustment laws are still in the proposal or development phase. So how do we know what kind of impacts these policies would have on emissions or on the global economy?

David Weisbach (08:21):

Sure. The way that carbon taxes and border adjustments are commonly studied is people build a big model of the economy. So the model tries to represent all the different sectors in the economy and how they interact, you know, look at a given sector and see what its imports are, see where it’s buying those imports. And it’ll kind of model all those things going on in the economy. It’s all done computationally. And there’s been, I think literally hundreds of published model runs that try to simulate the effects of carbon taxes, how much leakage there would be. And then what happens you put on border adjustments. The range of outcomes is surprisingly narrow, which is: expect leakage somewhere in the range of sort of 10 to 20% or something like that. Maybe 5 to 25 might be the broadest range you might expect. What that means in terms of numbers is for every hundred tons of emissions reduction in the United States, if that were the taxing region, let’s say, you would expect to see say 20 tons of emissions increase in nontaxing regions,

James Lawler (09:26):

So small, that seems fairly, or what do you, how do you understand that number? Is that a lot or a little?

David Weisbach (09:33):

Both. Right? Which is, it’s not very large in terms of the overall effectiveness of the tax. It’s not going to say us putting on a carbon tax is futile because it’s all the emissions are just going to shift off shore. And that sense it’s small, but in another sense, it’s big in the sense it’s going to be concentrated in particular industries. So, 20% leakage economy-wide might mean a lot of leakage in the steel industry or the cement industry, right? So it’s kind of both big and small. You might see some very effected industries, but it’s also telling us that a carbon tax is not futile.

Katherine Gorman (10:05):

But if we add border adjustments to the carbon tax, then that could compensate for this 20% or so leakage. Right?

David Weisbach (10:10):

Right. Now this just goes back to what Adele was just saying. So when we add a border adjustment, we still have a tax that’s going to suppress the price of energy, right? That is, whether it’s producers buying energy to use from production or me buying steel to consume, we’re reducing the demand for energy either way. And that’s going to suppress the global price of energy. And what that does is it creates an incentive to increase consumption abroad, right? And that’s what Adele, I think, referred to it as a fuel price effect. And that doesn’t go away when you add a border adjustment. And so to some extent, we think border adjustments don’t really solve one of the fundamental problems with carbon taxes, which is that the goals of these taxes to suppress domestic demand by raising the price of energy, but then that’s going to always lead to, or should lead to increases in use of energy in foreign countries. So I think the fundamental economic challenges are not getting at one of the core problems with carbon taxes, or regional carbon taxes.

James Lawler (11:12):

To what degree is that effect actually realized, or do we know?

David Weisbach (11:16):

The consensus is I think somewhere around a third, so leakage would be reduced somewhat, but not all that much.

Katherine Gorman (11:23):

So David, we understand that you and your colleague Samuel Kortum have a way to address this, that you wrote about in the US Energy and Climate Roadmap report that was published by the University of Chicago’s energy policy Institute. Can you tell us about that?

David Weisbach (11:40):

There’s an earlier stage of how fossil fuels enter our economy, which is on extraction. What that does is actually increase the price of energy we’ve seen in foreign countries, right? Domestic extractors will have to pay a tax when they extract the energy and sell the energy. And therefore they sell it at a higher price. And we think about energy as globally traded, you know, this sort of a single market price of energy, particularly for petroleum, but to some extent also for gas and coal. So any domestic tax on extraction that increases domestic prices of energy will increase global prices of energy. Right. And what that does then is it doesn’t create an incentive to increase the use of energy abroad because prices of energy have gone up, but it doesn’t solve the problem on its own because it creates another incentive. It creates an incentive to increase extraction abroad, right?

David Weisbach (12:30):

So you think of conventional taxes on production or consumption as lowering the price of energy and increasing production or consumption abroad. And you think of a tax on extraction as raising the price of energy and increasing extraction abroad. And then what we can show is if you combine these two taxes in clever ways – you combine a tax on domestic extraction, say at half the rate you want to impose and a tax on domestic production or consumption at the other half – then these two taxes offset in their effects on the price of energy seen in foreign countries. And so by combining the taxes in kind of clever ways, you can control how they affect the price of energy seen abroad and therefore how the taxes affect activities abroad, whether it’s extraction or consumption or production.

James Lawler (13:16):

And effectively leakage as a result.

David Weisbach (13:20):

Right. So what you can do is by combineing them in clever ways, end up with a much better result than any one of these taxes alone, because you’re using them to control what foreign actors see in terms of the change in the price of energy. And when you combine the taxes in this way, you end up with a much more effective tax. Overall, you end up with vastly greater emissions reductions on a global basis than under the traditional approaches.

Katherine Gorman (13:48):

Although the economics are complex, David and Adele’s research suggests that it is worth pursuing the emissions reducing benefits of carbon pricing and border adjustments. Now let’s take a look at the next obstacle, the logistics. How do we calculate what a border adjustment should be? Is that even reasonable to try to add a tax or rebate to every product traded internationally.

James Lawler (14:11):

To get a sense for how this might be done, we spoke with Dr. Brian Flannery and Shuting Pomerleau. Shuting is a climate policy analyst at the Niskanen center, which is a think tank, and in the summer of 2020, she published a white paper reviewing how border adjustments could be implemented. Brian Flannery is a visiting fellow for the think tank Resources for the Future and the co-author on a policy guidance report and framework proposal for developing World Trade Organization, or WTO-compliant border adjustment mechanisms. All of these reports are available on the Climate Now website, climatenow.com.

Katherine Gorman (14:54):

So let’s talk about the challenges of implementation. Is the idea that we actually figure out the greenhouse gas emissions required to produce every single product that is internationally traded?

Brian Flannery (15:05):

I think that most people have recognized it’s probably not a good idea to try to address everything. It’s just, there are too many products. There are too many nations. There may be too much paperwork, too much bureaucracy. So there tends to be a focus on those sectors that are the most greenhouse gas intense. The EU put its emissions trading system, ETS, mainly on these heavy duty industries like cement, steel, chemicals in some cases, but they left out things like transport in part because they already tax it so much. I think if the US were to do something I think we would include the oil industry, the gas industry, the coal industry, and fuels, which the EU does not. So the question is, what do you limit it to?

Katherine Gorman (15:49):

And just to clarify here, the European Union’s Emissions Trading System or EU ETS, is an existing policy for the EU that regulates emissions using a cap and trade system. But Shuting, in your report, you reviewed several bills and proposals on border adjustments. Can you address the question that Brian brought up by summarizing the various proposals for how we decide what should and should not be accounted for?

Shuting Pomerleau (16:15):

Yeah so I would say the existing carbon tax bills generally include a border adjustment section, and the way they approach product eligibility is really to either name a list of carbon intensive and trade exposed goods, like Brian just mentioned, or they set an arbitrary threshold. Like, so if your energy intensity and your trade exposure is above a certain threshold, you will be considered eligible under the border adjustment. I would say Brian’s point just now, like how to really balance the trade-off between making sure such a mechanism is administratively feasible, right. We’re talking about lots of products across many industries from many different countries. We’re talking about product level. I can’t emphasize how important that concept is. We’re talking about product level emissions and then cross that with countries and industries. So unlike a sales price of a specific product, the emissions of a specific product is not readily available. You can’t just look at a laptop or a car or a steel product and say, oh, I know how many emissions are associated with such a product.

James Lawler (17:31):

So I’d love to just get at this concept a little bit more clearly. So the challenge with products is you have shipping containers that arrive at ports, right, with a huge diversity, potentially, of products. You could have cars in there maybe, you could have like chips, you can have washing machines. I mean, who knows what you have, right? And so the concept is that we’re going to assess an adjustment on a per product basis that somehow accurately reflects the emissions that went into the production of each, not only each product, but potentially each constituent part of each product, and come up with some fair assessment. It just seems like impossibly complicated and logistically nightmarish, and would grind all trade to a halt globally, overnight. So how is my thinking about that wrong? Or is it right?

Brian Flannery (18:26):

No, your concern is real and many people share it. It’s kind of a nightmare scenario. But I don’t think it has to be that way. Trade and the WTO have a long experience with something called the value added tax (VAT), which is a lot like what we’re talking about actually, because every product has a value added tax in Europe, but it’s rebated upon export and imposed upon import. It’s easy to do because you just ask what’s the price and you add the VAT to it. But I think the question is, a) how do you determine a price for emissions? And then the next question is how do I allocate it to products? And I think the trade people really understood the issues about what’s WTO compatible and a lot based on issues like value added tax, but they didn’t understand that people in industry know how to measure greenhouse gas emissions very well.

Brian Flannery (19:16):

We’ve been doing it for decades on a facility basis in the EU, the EU ETS use similar methods to impose a limit on emissions from facilities. So we know how to do that. Well, the next issue is how do I allocate it to the products it makes? And how do I account for the emissions that are associated with greenhouse gas intense products in the supply chain, in particular electricity, fuels for thermal energy, and greenhouse gas intense feedstocks. But our approach says for a tax, if you’re going to tax these things, here’s what you do. It’s an upstream tax. We impose it on the carbon content of all fossil fuels. And we know what those are very accurately – coal, oil and gas – and on greenhouse gas emissions associated with producing them. For the supply chain, and we define something that’s GGI, how much carbon content is in your crude oil and what process emissions occurred. And now we ask what is the carbon that was associated with the electricity you purchased and the fuels you used. It’s a method probably more detailed than to go into here, but it is precisely equivalent to VAT, except it’s not paid at every stage of transformation. It’s actually, the more we look at it, the more we have come to the conclusion that this is just accounting, and we know what the numbers are we have to account for.

Katherine Gorman (20:36):

You mentioned the GGI. This is the Greenhouse Gas Index that you propose to decide which products should qualify for border adjustments, right? So how would this index be used?

Brian Flannery (20:45):

We devised an index, which basically measures how much CO2 is emitted, how much tons of CO2 are emitted per ton of product. And we devised a rather arbitrary cutoff. We said, if it’s more than half a ton of CO2 per ton of product, it’s covered, eligible for export rebates, subject to import charges. If it’s less, it wouldn’t be covered. Now we’re flexible on just where that boundary is, but that pretty much covered the major commodity goods of the major, big sectors that are energy intense. So that was our limit.

Katherine Gorman (21:18):

And then, how do you calculate how much CO2, how much carbon dioxide, is emitted, a per ton of product?

Brian Flannery (21:25):

It’s two things. We would base our evaluation of GGI on, for these products like steel, on what we call the core product, the first transformation ore, or recycled materials, into what they call raw steel or unwrought aluminum. That’s where most of the energy and greenhouse gas emissions occur. After that you’re fabricating it. We would count the emissions there, but we wouldn’t need to go into all the detail. We’d simply allocate those smaller emissions, according to how much of the core product is in each product. So it is a matter of accounting, but I think it’s straightforward.

James Lawler (22:02):

Okay. So I think I’m following you when you’re describing that it’s fairly straightforward with these larger commodity like products, you know, steel, cement, et cetera, but there’s a lot of other products that would be, you know, on which a carbon border adjustment could potentially be assessed. Aren’t there?

Brian Flannery (22:22):

Well, there could be. And I think that’s a question again of where your limit is. For instance, there are some who would like to apply it to automobiles, others who think that’s a bridge too far. I don’t know the answer, but I think perhaps it’s possible. But at that point, another set of complications come in, which Shuting is probably at a better place than I, which is, products that go into an automobile come from multiple countries and cross borders many times to the produce the frame of the door and then go someplace else to have, you know, the handles put on. And then back again, somewhere else. Frankly, I think supply chain issues could be a huge impact with systems like this. And so how we address these multicomponent products, I think is another issue. And country of origin, where did this product come from? But again, it’s a question of, can we hit the main items that are important and how much administrative complexity and cost is it, not just to the government, but to the firms.

James Lawler (23:19):

Right. Okay. And then Shuting, you’ve been thinking more about these more complex products and how we account for those. Is that right?

Shuting Pomerleau (23:31):

Yeah. I think Brian was absolutely right to really make an analogy of a carbon border adjustment to a value added tax. Now, the accounting part is really similar. If you look at a value added tax, it’s a consumption tax. So producers along the supply chain, they remit a value tax liability to the government minus any previous VAT liability that previous producers have already paid. So you could think of it as like an additive tax liability for a VAT. Now, the reason that a carbon border adjustment is similar is with like, say a product like you just talked about like steel, very primary goods, they go into the production process to produce some intermediary goods, right? And eventually it might go into the production of final goods, like a car. And so we’re looking at the supply chain as a chain of additive, carbon emissions, each producer along the supply chain, they’re producing something, they’re putting together a product with different components, whether it’s imported or domestically produced.

Katherine Gorman (24:49):

So with these products, even if the accounting is possible with some kind of additive system along the supply chain, wouldn’t it simply be overwhelming to try to trace all of the places that all of the parts of this product have been. And then even if we can do that, who’s going to report the data. Is it the factories? Is it the governments of the countries that those factories operate in? It seems like even if it were somehow possible to do all this accounting for these more refined products, how would we regulate the reporting from multiple countries and make sure that the numbers are correct?

Shuting Pomerleau (25:22):

There is a useful way to address this complex international trade, the emissions embedded in the international trade. Jennifer Hillman, the former WTO appellate body member, back in 2013, she wrote a report analyzing how would a border adjusted carbon tax comply with the WTO rules? And then in her analysis, she believes that you saying a ‘like product’ approach might be the safest options for a carbon border adjustment or border adjusted carbon tax to comply with the WTO rules. A like product approach is really: treat an imported product as if it was produced locally based on the best available technology or predominant production technology. So the question here is really converting from accounting for actual emissions associated with a specific product from one of the say, many countries that the United States is trading with, to really matching an imported product to a domestically produced product, and then say, okay, we’re treating imported product and local locally produced product the same. We’re assuming that their emissions might be the same. And then we levee a carbon tax on the imported product.

James Lawler (26:50):

Okay, so you mentioned just now that in addition to making this logistically feasible, there’s this need to make border adjustment policies legal within the world trade organization framework. And with that in mind, I want to ask about a bill that has garnered a lot of attention since its introduction in the US Congress in July, 2021, that is the Coons-Peters bill, otherwise known as the Fair Transition Competition Act. Shuting, I wonder if you could describe what this bill is and why it’s been getting attention when all the other recent carbon tax and border adjustment bills in Congress have not.

Shuting Pomerleau (27:30):

Yeah, definitely. So my understanding is that the democratic lawmakers absent of a carbon tax in the United States, they’re trying to think of ways to incentivize our trading partners and US domestic producers to continue to decarbonize their productions. So the bill is really trying to look at the US domestic manufacturers, what additional costs they’re subject to under the existing regulatory, greenhouse gas emission policies. And then they’re trying to convert the cost across the industries into a price per ton of emissions, and try to impose that number on eligible imported goods. The reason that I think it’s gaining some traction is because there’s this narrative in the climate policy world, that one country alone can’t solve climate change, you need global efforts. So a lot of policy makers and experts are saying, well, it’s not sufficient if just the United States is doing something. We want other countries to join us and to really have ambitious climate policies.

James Lawler (28:51):

But, to be clear though, the US doesn’t have a carbon price, right? So we’re not actually doing anything, but we’re adding a carbon border adjustment to other countries imports?

Shuting Pomerleau (29:04):

Yes, you’re spot on James. So the key to a carbon border adjustment is we need a domestic carbon tax. Otherwise you don’t have anything to adjust at the border, and you’re right James, that there’s no uniform or national climate policy in the United States currently to address greenhouse gas emissions, it’s just a patchwork of regulations, performance standards, subsidies at the federal and regional and local level. So I think without a carbon tax domestically, however you call it, carbon border adjustment, importer pollution fee, I think it’s actually a tariff that you’re trying to impose on imported goods.

Katherine Gorman (30:01):

So while figuring out the logistics of border adjustments, we identified even more complexities in that it might be tricky to make a border adjustment policy that is legal in terms of international trade. Because David Weisbach specializes in tax law and Adele Morris specializes in economic policy. We wanted to ask them more about these issues.

James Lawler (30:22):

So I want to move on to the legality, like around carbon border adjustments. David, you’re a lawyer. Tell us about the legal considerations here.

David Weisbach (30:34):

You got a couple hours?

James Lawler (30:37):

In brief.

David Weisbach (30:37):

So the concern is that that border adjustments can act like protectionist measures, either import tariffs or export subsidies. And the WTO is designed to prevent countries from having protectionist measures, either subsidies for exports or import tariffs. And so the question is going to be whether a border adjustment complies with the WTO rules. And the problem is that the rules are archaic. They’re mostly written in the fifties and not with this in mind. And so we know we can do border adjustments on value-added taxes, cause those were included in the legislative language, but border adjustments on a good, that was produced with a carbon or produced with fossil fuels are not something that was really contemplated in the legislative language has implemented by the WTO. And so you’re kind of stuck trying to squeeze these border adjustments into various rules or exceptions to see whether they can be not treated as a tariff or a subsidy.

David Weisbach (31:38):

And that’s kind of the, you know, really, really big picture version of it. And then when you talk to people who specialize in this, who do this for a living, I think the consensus is that the WTO is not going to step on anyone’s toes here so long as the border adjustment is reasonably implemented in well-intended. That is the WTO is going to think this is too important to invalidate, but they’re not really sure because the rules are ambiguous in terms of how they apply in this context. And so, you read the language and map it on to this case and you really can’t quite figure out how it should work.

James Lawler (32:15):

Makes sense. So Adele, I just want to clarify something because it didn’t make any sense to me when I read it and maybe you can illuminate it. So in July, there was this new legislation proposed in Congress to impose this fee on carbon intensive goods. Like, you know, this carbon border adjustment in the United States, but we don’t have any carbon pricing. So I didn’t understand, like in what context or what world does that make any sense at all?

Adele Morris (32:46):

Okay. Well, okay. So the most generous interpretation, a generous interpretation of the motivations, it’s a response to the EU talking about this policy, and it’s a way of starting the conversation domestically about a carbon tax. But, if you look at the legislation and how it’s crafted, there’s a lot of peculiar things in there. For example, it wants to adjust regulatory costs, right? So thinking about making a more fuel efficient car owing to some regulation, okay, it’s more costly to do that. You have to use more aluminum than steel to down-weight the weight of the car so it’s more fuel efficient, right. Stuff like that. Okay. But then it takes those regulatory costs and multiplies them times the emissions that are emitted during the process of that manufacturing. Well, the emissions in making the car has nothing to do with the costs of inputs that are higher on account of, they had to down weight from steel to aluminum. So like there’s some kind of goofy formula stuff in there that needs to be straightened out. And I think they’re going to figure this out, but, it illustrates the challenge of amalgamating, all of these disparate cats and dogs of regulations and, you know, state level policies and all that stuff. In my opinion, it really only makes sense to do a border adjustment when we have our own clear federally-imposed carbon price, you know. Anything other than that is extremely hard to make much sense of it, in my opinion.

James Lawler (34:33):

And, and so why aren’t we just doing that? Why aren’t we discussing carbon tax legislation instead of border adjustments?

David Weisbach (34:39):

My take is, again is, and I’m in Chicago so my DC take may be completely wrong, is that the Biden folks have given up on a carbon tax, that they’re going to do this all through regulations and subsidies. And they say, well, that’s just, that’s just a different way of doing the same thing that a carbon tax does. It’s imposing costs on industry to reduce emissions. And so we want to – just like, we would want a border adjustment on carbon taxes – we want border adjustments on all these regulations. And as Adele was just saying, it’s going to be really hard to do that, but I think they’re thinking carbon taxes and regulations are substitutes for one another in terms of emissions reductions and therefore border adjustments belong on both.

James Lawler (35:16):

And is that true or not true?

Adele Morris (35:19):

I think it kind of conflates two things. Like, regulatory costs are costs associated with the reduction of carbon, right? A carbon pricing system is a cost associated with the remaining emissions, right? The emissions that weren’t reduced. So economically there’s a fundamental difference between regulatory costs and costs associated with the incidents of a carbon tax or similar cap and trade program.

Katherine Gorman (35:53):

Okay. So let’s say legislators amend the problem with the math logic. Still, as you say, and adjustment based on regulation instead of a single carbon price is going to be really hard. So again, why would the current administration be giving up on a carbon tax? What do you think is the political motivation for trying to use regulations instead?

Adele Morris (36:14):

Well, I think there are three reasons I think there is a certain hesitancy amongst the Democrats for a carbon tax. And it’s not generally a lack of appreciating the economics because you know, my profession is loud and clear on that. Number one is, President Biden promised not to raise taxes on anyone earning under $400,000 a year. And the economic incidence of a carbon tax would fall on individuals that include people who make less than $400,000 a year. Now, obviously you can use the revenue from a carbon tax to redistribute that in a progressive way, but I guess they’re feeling like that’s not part of their pledge. Second is, there are folks on the progressive left who really think the climate challenge is too big to rely on market forces. And you know that we’ve got to go straight to, you know, keeping it in the ground.

Adele Morris (37:18):

And then also there are folks in the environmental justice community that don’t support carbon pricing because the belief is that regulatory approaches on carbon are more likely to help air quality in their communities. And I’m sure it’s much more complicated than that, but I think there is a tepid support if any, on the far progressive left for carbon pricing, even if there is some lukewarm support among some Republicans for carbon pricing. I think the challenge though is, okay, you don’t want to do carbon pricing, you want to do regulation, well, what’s the environmental equivalent in the regulatory world and we’re not anywhere near close to that. I mean, even if they come up with a clean electricity standard, what are you doing for the rest of the two thirds of our emissions inventory? Are we going to do standards in every sector? How’s that going to work? And, you know, you might say, okay, well, a clean electricity standard is an easier legislative lift, but it’s not environmentally equivalent. You got to have that plus additional legislation to target the whole rest of the emissions inventory. So I still think a carbon price has a chance. It should be given a chance. I wouldn’t give up without trying, but then I’m not a political advisor. So maybe they’re listening to smarter people than me.

David Weisbach (38:43):

No they’re not. Not a chance.

Katherine Gorman (38:55):

That is it for this episode of the podcast. You can find other episodes, watch our videos and sign up for our newsletter at climatenow.com. And if you want to get in touch, email us at contact@climatenow.com, or tweet at us @weareclimatenow. We hope you’ll join us for our next conversation.

Further Reading:

The Design of Border Adjustments for Carbon Prices – Samuel Kortum and David Weisbach (2017)

For carbon, is the EU proposing a border adjustment or a tariff? – Shuting Pomerleau (2018)

Changing Climate for Carbon Taxes: Who’s Afraid of the WTO? – Jennifer Hillman (2013)