Climate Now Episode 9

June 25, 2021

Net-Zero by 2050 with Eric Larson

Featured Experts

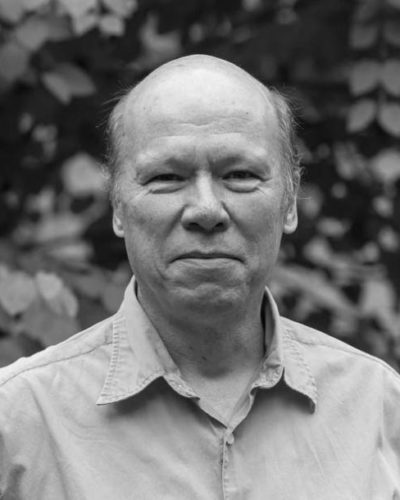

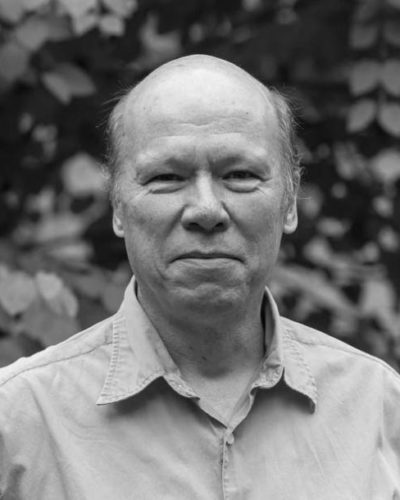

Eric Larson

Princeton Andlinger Center Senior Research Engineer

Eric Larson

Princeton Andlinger Center Senior Research Engineer

Dr. Eric Larson is a Senior Research Engineer at Princeton’s Andlinger Center for Energy and the Environment and a lead author of the Net-Zero America Report – a Princeton University research initiative that provides five pathways to achieve net-zero emissions in the US by 2050.

He is also a Senior Scientist at Climate Central, a nonprofit that researches and reports on the science and impacts of climate change.

Featured In:

In this Episode

What are the possible paths and necessary steps to achieve net-zero emissions in the United States by 2050? Which energy sources could sufficiently decrease our reliance on natural gas and oil to meet that target? And how much will those new energy sources need to scale from where they are today?

Dr. Eric Larson is a lead author of the Net-Zero America Report – a Princeton University research initiative that presents five possible pathways to achieving net-zero emissions by 2050 – and Senior Research Engineer at Princeton’s Andlinger Center for Energy and the Environment.

In this episode, Dr. Larson takes Climate Now hosts James Lawler and Katherine Gorman through the various pathways to net-zero, including the technologies that could help us achieve it.

Related Media:

Research Ep 1

Net-Zero by 2050

Pledges to achieve “net-zero” emissions are proliferating from companies and countries alike. However sincere these commitments may be, they rarely include specific plans to achieve that ambition. The Net-Zero America Report from Princeton Universi

A Climate Change Primer Ep 2

How dirty are we?

Global greenhouse gas emissions reached a staggering 52 gigatons of CO2-warming equivalent in 2020. Our episode puts this number into historical context, parses our global emissions by country and economic sector, and delves into the key economic and demographic drivers of emissions worldwide.

Climate Now: Jun 7, 2021

Climate Projections with Sergey Paltsev

Dr. Sergey Paltsev, Deputy Director of MIT’s Joint Program on the Science and Policy of Global Change, spoke with Climate Now hosts James Lawler and Katherine Gorman about climate projections and the tools he and his colleagues at MIT use to communicate

Climate Now: Jun 18, 2021

Carbon Capture 101 with Howard Herzog

According to the IPCC’s 2018 report, carbon capture and storage – in addition to a significant reduction in emissions – will be necessary in order to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees above pre-industrial levels. But what is carbon capture,

Episode Transcript

Katherine Gorman (00:02):

You are listening to Climate Now. I’m Katherine Gorman

James Lawler:

And I’m James Lawler.

Katherine Gorman:

So there’s been a lot of buzz lately around this idea of net-zero from company sustainability plans to government policies. But what does that even mean? And is it even achievable?

James Lawler (00:19):

Yeah, I mean these net-zero, carbon neutral terms are getting thrown around more and more and they look very flashy. They look very attractive. I mean, who wouldn’t want it?

Katherine Gorman (00:27):

Yeah, absolutely. Like I’ll take two, please.

James Lawler (00:31):

And so basically the idea, of course is, net-zero simply means that you’re only admitting as much carbon into the atmosphere as is being taken out of the atmosphere. And that’s kind of been articulated as a target, but how real it actually is and how, sort of, rigorous the plan is to get there, you know, varies drastically, depending on who’s adopting those plans.

Katherine Gorman (00:53):

To dig in with us more on this topic today, we have an amazing expert, Dr. Eric Larson. He’s a senior research engineer in the Andlinger Center for Energy and the Environment at Princeton University. And he’s one of the authors of the net zero America report that describes how the US can reach net zero as a society by 2050 Dr. Larson, thank you so much for joining us.

Eric Larson:

Pleasure.

Katherine Gorman:

So the report is a whopping 345 pages, but it’s not like other scientific reports or academic papers. This is sort of more set up, kind of like a PowerPoint with lots of graphs and images and detailed infographics, walk us through it.

Eric Larson (01:33):

Yeah, there’s been a lot of studies out there to try to sort of paint pathways to net zero or to low carbon in any case, but we felt what was missing is, is sort of a real visceral picture of what it actually means to get to net zero emissions. The models tend to be done at a fairly high level, a little bit abstract. And so we decided to do modeling that would really paint a much more vivid picture to try to understand what the, both, what the opportunities, but as well, what the challenges are to actually getting to net zero.

James Lawler (02:07):

And you articulate in the report, this is I think more or less a direct quote from the report “despite growing government and corporate net zero by 2050 pledges, there’s little detail on execution costs and impacts.” And so my question is, to what degree are the slew of current pledges that we are seeing out there real, sort of accomplishable, clearly sort of planned out pledges of action versus sort of greenwashing or PR or fluff?

Eric Larson (02:39):

I think in terms of the ambitions that are being set, there’s seriousness behind it. On the other hand, I think many of the entities that are making these pledges really don’t have an idea of how they’re going to get there. And what our report does is, in a sense, is to illustrate what are the actual steps that you would need to take in order to execute on, on the ambition.

Katherine Gorman (03:03):

So how did you determine these steps? What’s the methodology that you used?

Eric Larson (03:07):

Okay. The basic approach was to start with energy service demand, projections that are sort of official projections of where, where we expect to go as a country. And so energy service demands means things like vehicle miles traveled, square footage and buildings that’s, that’s heated and cooled, you know, tons of steel that we make and other industrial outputs. Those are the services that we want from energy. And then we said, how are we going to meet those demands? And we set up our modeling, to, to be able to meet those demands, but it’s a model that based on meeting the service demands, it optimizes the mix of technologies that are available to the model that minimizes the cost of the overall energy system over the whole transition.

Katherine Gorman (03:54):

And so the model really focuses on three different variables, right? Electrification, renewable energy and biomass?

Eric Larson (04:02):

Right. What we did was to look across several parameters in the energy system, that, that we sort of understand to be critical in any kind of a transition. One of those is the extent to which we electrify the final energy use. If, for example, electrification of vehicles or electrification of heating in homes is a big one, which takes us away from using natural gas or oil for heating inside of homes. So we had two different levels of electrification that we explored across our five scenarios. And then another key variation across the scenarios is how much we rely on solar and wind in the future. Solar and wind are, the costs have been coming down dramatically in the last decade. It’s promising that that’s, uh, one of our least costly sources of electricity, but there may be challenges to deploying enough wind turbines and enough solar panels to, to get to the levels that we might want.

Eric Larson (05:03):

And so we looked at a case where we constrain the growth rate of wind and solar to only what we’ve accomplished historically. So that was kind of a lower bound on the renewable side, and then on the upper side, we basically required the model to get to a hundred percent renewable energy by 2050. And then the last variable that we played with was the amount of biomass that we allow in the energy system. And biomass is, uh, is critical in our scenarios because it’s a source of carbon that comes as a result of growing plant matter. And that takes CO2 out of the atmosphere. And so when we use that plant matter for energy and put that carbon back into the atmosphere, we have a carbon neutral system, right? And, and, that carbon is very important in making fuels, which even though we do a lot of electrification, the, in these net zero futures, we still need some fuels for things like airplane fuel and, and others.

Eric Larson (06:04):

And so we explored the idea of two different scenarios for biomass. One was where we said, we don’t want to impose any led change in the planned use from what it is today, because there are concerns about converting cropland into energy crops, from food to fuel. And then in the high case, we allowed, there’s been a big study that’s been done and, and updated every few years by the department of energy and the department of agriculture exploring what the maximum potential for bioenergy for biomass production might be for energy. And so in the high case, we adopted that range of bio energy supply, and that includes, it does include some conversion of crop food, crop, land, and pasture to energy crops.

James Lawler (06:49):

And then, so in the report, you use the model to explore five different pathways to get us to net zero by 2050, there’s high electrification and low electrification pathways.

Eric Larson:

So that’s two E plus and E minus.

James Lawler:

E plus is high electrification and E minus is low electrification.

Eric Larson (07:04):

And then in the case with renewables, we, we adopted the high electrification on the demand side, the E plus, and then we, we had an E plus R E minus, which represents the constraint renewable growth, and then an E plus R E plus, which represents the a hundred percent renewable by 2050. And those, again, both use the constrained biomass supply. And then the fifth scenario was the case where we looked at the E minus demand side, which is a less electrification of vehicles, which you would anticipate more demand for fuels. And so we allowed in that case to allow more biomass into the mix.

James Lawler (07:46):

You’ve essentially modeled the extremes along three axes, electrification, biomass, and renewables.

Eric Larson (07:51):

Yes, that’s a, that’s a good, good summary. And I, I should say that we don’t believe any of these will be the actual one that gets us to net zero. It will be, if we get there, it’s going to be some permutation of, of these, right?

James Lawler (08:04):

Yeah. And so on the upside folks, there’s five ways we can do it at least.

Katherine Gorman (08:08):

So we’ve heard from some scientists who believe that there is no way that we can get to net zero without a wide scale adoption of nuclear. And this report doesn’t seem to suggest that, why?

Eric Larson (08:19):

As I mentioned, the modeling is done to minimize costs, and nuclear is relatively high costs today. It’s not able to compete with wind and solar, even, even when wind and solar are variable and you have to have other costs to accommodate that variability, but that’s the basic reason. So if we can get advanced nuclear that’s much less costly, you know, that might be the way we go in the longer term. So nuclear is in the mix and all is allowed in the mix. And all of these scenarios, the only one where it really plays a significant role, and it is a significant role, is in the, what we called the E plus RE minus.

Katherine Gorman (09:00):

So high electrification, low renewables.

Eric Larson (09:03):

Where we don’t build out the solar and the wind at the rate that the model would prefer to build it, if it were unconstrained and there we need nuclear as, as the option to supply the levels of electricity that are demanded across the economy. It’s, it’s a heroic rate of expansion of nuclear from say 2035 on, there’s very rapid expansion of nuclear. I should mention that the expansion rates in all of the, across many of these technologies are historically unprecedented, including the nuclear build in that case.

James Lawler (09:39):

Yeah, so that’s a good segue, I think, into the next, my next question, the report calls for major investment on the order of, and this is a quote from the report “$2.5 trillion in additional capital investment to energy supply industry and buildings and vehicles over the next decade, relative to business as usual with trillions more to 2050, that must start now with consumers paying back the costs over the next several decades.” I wonder if you could explain what that means, like who would be making these investments and how would consumers be paying them back? You know, how well do we understand the risk profile of the investments that are kind of called for here?

Eric Larson (10:18):

There’s a lot in that question. So we did estimate the, you know, the overall, the modeling was done to minimize the overall costs of the energy system. And when you look at, look at what the cost is on an annual basis, so what we spend annually on energy as a fraction of GDP going forward, it’s on the order of 4 to 6%, something like that across all the years that going out into the transition and that’s, that’s actually in the ballpark or even lower than, than it’s been historically in prosperous times for the US. So in, typically in the last say 20 years, when we haven’t been in a recession or we haven’t been dealing with oil price shocks, we’re in the order of 5 to 8% of our energy of our spending on energy as a fraction of GDP. And so we’re talking about 4 to 6% here, so it’s in the same, in the same ballpark.

James Lawler (11:17):

And that spending on energy, do you mean everything from people filling up their cars at the gas station to people paying their, um, you know, fuel oil bills and everything and investment of states into transmission infrastructure?

Eric Larson (11:31):

Yes. Yes. All of, all of that, that’s the whole, all the spending on, on energy. What’s different from the past is that as we go forward, in these net zero transitions we, a lot more of the spending is upfront capital. It’s like buying a home, right? You, you have to put capital up front, you have to borrow money. Typically, the percent of number that I was referring to is our mortgage payment, but we have to have the upfront capital to build solar panels, the wind turbines, nuclear plants, what have you, that has to be invested. That’s not a cost, that’s an investment. And then that gets paid off over time by, by, consumers. And as far as who invests that capital, it’s going to be a mix of consumer investment. For example, if I go out and buy an electric vehicle today, I’m probably paying a little bit more than if I bought a gas vehicle.

Eric Larson (12:24):

So that’s an extra capital investment that I’ve had to make. All right, but maybe there’s a government incentive, which there are in the case of, in some places that buys down that cost of the EV. So in that case, the government has put in some of them investment and our estimate of that, that 2.5 billion, trillion, sorry, uh, big numbers that represents maybe a 5% increase for the consumer in terms of consumer spending. So, in particular electric vehicles, in homes, heat pumps are the technology that would electrify heating in a home. And that has an extra cost associated with it, so 5% of five to 10% higher costs for the consumer. If there are incentives provided by the government on the supply side of the energy system, it’s a much bigger investment in capital, maybe doubling what the business as usual is. So rather than building, for example, gas fired power plants. Now we’re building solar and wind and, and, other alternatives. And the capital invested for those is, is roughly double what the business as usual investment would be.

Katherine Gorman (13:36):

So could you talk us through what kind of investments need to be made right now. And, and, what’s the risk of these early investments?

Eric Larson (13:43):

It turns out that in the 2020s, across all of the pathways, we do more or less the same thing to set us up for the longer, for the longer term. Things that are done in the 2020s are going to, can be done with a fairly high degree of confidence that they’re going to return value in the longer term. So in terms of a risk profile that you’re talking about, I think the investments in the 2020s are, with some exceptions that I’ll mention, are pretty solid investments that should be made.

Katherine Gorman (14:15):

Great. High reward, low risk. I mean, where do I put my money?

Eric Larson (14:18):

So that includes going to electric vehicles, that includes, uh, solar and wind build out at a, at, at a very rapid rate. The second category in the twenties is the idea of setting up enabling infrastructure to give us the options for even greater growth in the 2030s and 2040s. So that’s, for example, increasing, enlarging our electric grid so that we can add all of this solar and wind and, and more beyond in the next decade, uh, CO2 transport and storage systems are a critical part of all of our scenarios. Even the case where we go to a hundred percent renewables by 2050, even in that scenario, we actually have to do CO2 capture in order to have carbon available, to be converted back into a hydrocarbon fuels that we still need by building the infrastructure for CO2 transport and storage in the 2020s, that then sets us up to do lots of CO2 capture that will be needed in the 2030s and beyond.

Katherine Gorman (15:27):

So does that exist today, CO2 transport, or is that a new idea?

Eric Larson (15:31):

We do have a CO2 pipeline system in the US today, which many people aren’t aware of, something like 8,000 kilometers or 5,000 miles worth of CO2 pipelines. And these are, generally what they’re doing is,taking CO2 out of natural formations. And so there are pockets of CO2 in the subsurface that are pure CO2. They’re actually mining the CO2, putting them in the pipeline and shipping it down into, particularly the Permian basin in west Texas, and injecting it into oil wells to increase the production of oil. And over time, the CO2 ends up essentially staying below ground. So it’s not, it’s not going back to the atmosphere, but it’s being used specifically to help produce oil today. So we have experience and the oil and gas companies are quite familiar with shipping of CO2 around.

Katherine Gorman (16:29):

So, okay, so what’s the last category of investment in the twenties? The high risk category.

Eric Larson (16:33):

The last category is the one where there is a bit more risk involved, but it’s a, it’s a fairly small part of that 2.5 trillion. It’s something like $130 or $150 billion, and that’s investing to create options for the longer term for the 2030s and 40s. So that means investing in technologies that we basically understand the engineering of today, but they’re not at the scale that we could begin or, or maturity that we could go out and start building them. And in large quantities, that’s things like advanced nuclear technologies or biomass gasification to make hydrogen, which turns out to be an important technology and are in the 2030s and forties or electrolysis to make a hydrogen by splitting water, using electricity from solar or wind. These are technologies that we, we basically understand today, but need to be demonstrated at a fairly substantial scale and with multiple demonstrations to gain confidence so that when we get to 2030 and realize, oh, this path that we thought we were on, it’s not going to work. We need another option. So that’s the idea of option creation is the other pocket of investment in the 2020s.

James Lawler (17:50):

And what percentage is that of the 2.5 trillion or is that…. ?

Eric Larson (17:54):

It’s small, it’s $150 billion out of $2.5 trillion.

James Lawler (17:59):

So Jeff Bezos could do all of that.

Eric Larson (18:00):

Sure. Yeah and Bill Gates is working on some of it. I think, I mean, he’s, he’s got some investments in nuclear, for example.

James Lawler (18:15):

Eric Larson from Princeton University telling us about a recent report he co-authored examining pathways to a net-zero America by 2050.

Katherine Gorman (18:23):

Yeah, I feel like we’ve got a crystal ball showing us optional futures or different paths. We’ll have a more detailed net zero video on our website. And we’re going to have the opportunity to talk to experts in each of these different technologies on the show and in future episodes. That is it for this episode of the podcast. You can check out other interviews, watch our videos and sign up for our newsletter at climatenow.com. And if you want to get in touch, email us at contact@climatenow.com, or tweet us @weareclimatenow, hope you’ll join us for our next conversation.